Hunger For a Way Out

I denied myself and my body the care and compassion of feeding it. Now, I'm using food and cooking as part of my recovery from trauma.

Content warning: this essay has a few mentions of suicide and hospitalization, and a larger discussion of weight and unhealthy eating.

Eat and feed are similar words. They mean mostly the same thing. They are often used interchangeably, in the same breath. Both have an etymology of Germanic origins, which through iterations of Old English and Dutch, have resulted in terminology to describe the most basic functions of consuming to sustain oneself.

But as such, they are different words. Eat is demanding. It is active. Functional. You eat to get through the day so your stomach doesn’t growl and your head doesn’t spin. You eat when you are hungry and need to satiate yourself for the time being. Your mother tells you to eat, her voice straining, when you are a child and dinner is more than unappetizing.

Feed is different, still, from Eat. There is compassion in the word feed — the care of nourishing yourself and the people you love, with food. You feed yourself to savor taste and texture and the experience of a meal. You feed others to cherish this food in their presence. A dear friend who is a chef delightfully describes cooking and feeding both yourself and others as “intimate,” which it is; feeding yourself and others is a simple act of quiet, private love.

We eat to stay alive. We feed to build and sustain connection, community, and culture through food, cooking, and the time spent together at meals.

In July, I found myself alive, but not willingly. A daily antipsychotic medication I had been prescribed seven years ago, when I was sixteen, suddenly and inexplicably plummeted me into the depths of thick, viscous depression. I developed involuntary twitching in my face, a long-term effect of taking antipsychotics. The twitching can be permanent. The inside of my lips developed aching sores as my mouth rubbed and puckered around my grinding teeth. I cracked a tooth after grinding my teeth too hard for so long. I chewed gum and talked as often as I could to disguise the uncomfortable and odd movements. I damned my body, as I have always done, for betraying me.

I stopped taking the antipsychotic. I started taking a new medication, a mood stabilizer. It works, mostly.

Another common long-term effect of antipsychotics is weight gain and hunger. I have experienced both of these. I became not just an emotional eater, but a compulsory one who had certain rituals to eat more and more of certain foods. I ate quickly, often embarrassed at being the first person at the table done eating. Upon beginning the new medication, I noticed that I didn’t crave food, nor the certain routines of eating, nor feel the endless need to eat, and eat, and eat.

I had gained about eighty pounds on the antipsychotic by the time I stopped taking it. When I was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric hospital in late October, I had lost, in the span of a few months, about fifteen percent of my body weight. In the midst of sobbing in the crisis center, I told the nurse who took my vitals that I can always stand to lose some weight, anyways.

Cooking, for myself and others, is nothing short of a joy. It is inherently social — not only is food nourishing for my physical being but for my friendships and romances and relationships with my family. I cooked for my parents and sister when we were quarantined early in the pandemic to take the stress of feeding a family off of my mother. Now, I throw dinner parties and invite cherished friends who I want to feed. I split dinners with my roommate when I make more than enough for myself. I bring focaccia to a housewarming party, a strawberry dutch baby to a friend working at a bookstore, a bastardized pasta salad to a backyard cookout. My memories of others are marked by the meals we share.

I learned to cook while I was in college. In fraught attempts to lose weight, I often committed to extreme diets that more or less worked; usually less, because losing weight on the antipsychotic was as painfully slow as pulling teeth. One of these diets was a keto diet. For months at a time, I would cut out as many carbohydrates and sugar as I could from what I ate, replacing ingredients with alternatives and looking for recipes with high protein and fat contents. As a college student, purchasing ready-made keto food was not in my budget, if it was even available in the grocery store, so I cooked nearly every meal I ate to minimize the carbohydrates and sugar; while these diets always ended in my eventual return to a more normal diet and immediately gaining every pound back, I retained knowledge of basic cooking skills that I could continue from.

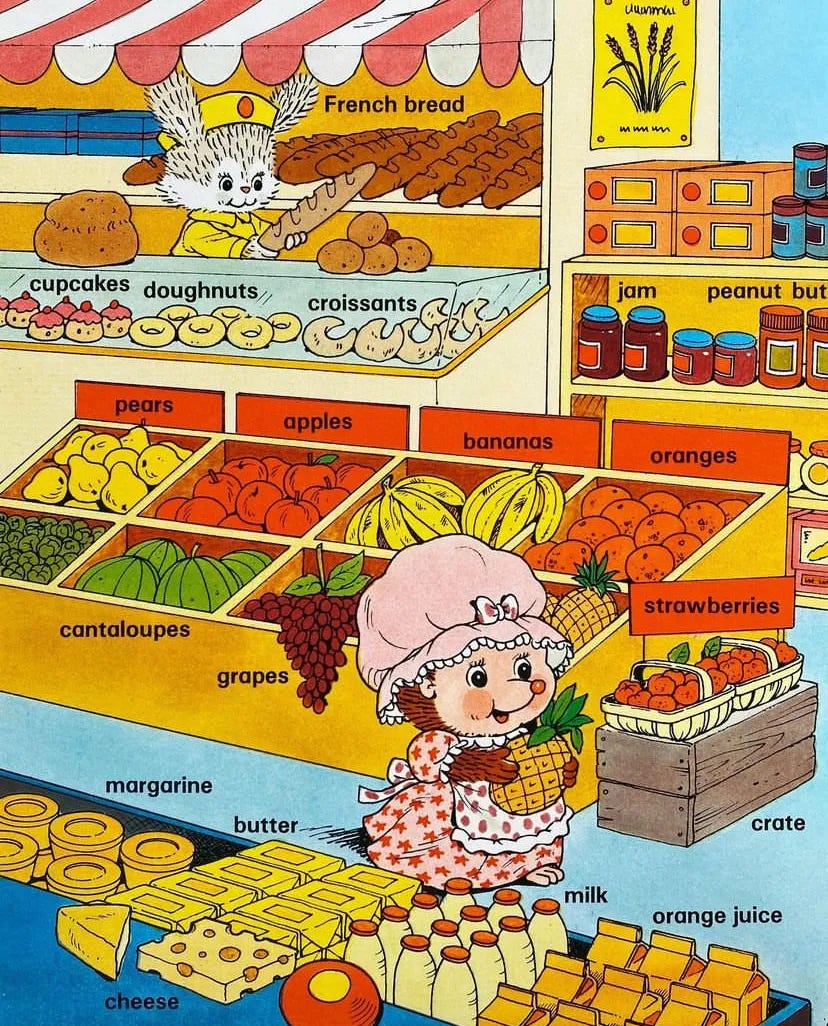

I have also since learned how to shop for foods that nourish your body properly. I avoid refined and processed oils and sugars, low-fat dairy products, white bread, most frozen foods, anything “instant,” and anything that could be easy to snack on for the sake of making myself cook at home instead of grazing. I stock up on fresh produce, fatty fish, sausages from the butcher, sourdough bread, whole milk and cheese, plain greek yogurt, fermented foods like kimchi and tinned seafood, fresh pasta, sea salt, and excessive quantities of good, rich, bright olive oil. I cut costs elsewhere in my life to pay for nice, good-quality ingredients to cook and feed myself with.

I often share my cooking online to extend this into the digital realm. I have documented years of meals. Some are better than others. Some are more or less visually appealing. All have nourished me, left me full, were learning experiences in the practice of cooking, and have connected me with people online. I share these meals and recipes candidly on my Instagram. Cooking on social media for a virtual community is, obviously, different from cooking for someone in reality, but the small interactions from compliments to critiques weave an ever-strengthened web of social engagement centered around the practice of feeding for one or for all.

My relationship with eating changed after I started the new medication. Without purposefully restricting myself, I consumed a meal a day, usually less; most of my calories were either from eating a social meal at a restaurant or from alcohol. I stopped having the energy to grocery shop, and in turn, stopped cooking daily as I lost the will and happiness in doing it; this should have been a canary in the coal mine that I was truly unwell. My speed of eating slowed to the point of me struggling to finish a meal, long after the dishes were cleared and the next course had arrived. What I did eat for meals included kalamata olives straight from the jar, tinned sardines with a fork, random granola bars from the CVS a few blocks from my office, single apples I threw in my tote bag, a little bit of half-and-half in a cup of coffee.

I longed for being able to eat, and my anger at myself grew when I couldn’t bring myself to eat, much less cook. I missed, desperately, the careful practice of cooking: the beloved trips to the grocery store, sourcing what I want to make from seasonal ingredients, the tactile sense of a knife prepping vegetables, the hot oil in a pan, the sounds, the smells that waft through the kitchen of my basement apartment, all of these small moments resulting in a meal. Something wonderful, fleeting, and soon, gone. I missed feeding both myself, and in turn, being able to show myself the same care, compassion, and intimate nurturing that I might to someone else I loved.

Upon leaving the hospital at the beginning of November, I was hungry. Needless to say, the hospital food was bad, and my body lamented the lack of vegetables I was served and became lethargic from the sheer number of cellophane-wrapped muffins I had sadly consumed in my tenure there. I arrived home to no groceries in my fridge, as I had not shopped for food in weeks prior to my admission.

Being released from the hospital is like standing at the base of a mountain, looking up to the faraway peak. I knew I had to put in the effort and energy to climb the mountain, representing my recovery from depression and years of untreated trauma that tormented me to the point of suicide. It is a daunting feat, and a part of me said that climbing wasn’t worth it; I’ll never really recover and I’ll always be burned by my past and my separate mental diagnoses. For me, making the choice to climb the mountain wasn’t necessarily an act of determination, but more a flight from the omnipresent fear of things getting bad again; in turn, I wanted to recover not just for myself, but so I could care in turn for my friends, my family, my partner, and other intrapersonal relationships. Recovery included many hours of intensive outpatient therapy, finding a long-term psychologist, continuing to adjust to my new medications, and finding joy in myself and the life I lead again. But these are bigger steps; they do not happen without making smaller ones, such as going to the grocery store and cooking yourself dinner.

I started feeding myself again. I took the time to decide what I wanted to eat, revel in the experience of cooking, and savored every bite of my meals. I felt a fullness I had forgotten for so long, not just in my stomach, but in my abilities to regulate my depression and function in my daily life. I felt proud of myself; I let myself feel proud of myself. I posted what I cooked to my Instagram. People noticed. My partner mentioned that not only were the meals I cooked good but I was excited and happy to spend some time in my day to feed myself. I don’t know if they know how much this small comment meant to me; for a person I care about to actively see me trying to care for myself through food and recognizing it.

Food has been a constant sense of stability in my life when for much of my life, I did not have any sense of what stability was. Even in the throes of my most miserable experiences, I could eat: always shaking small packets of iodized salt and fake lemon onto hospital food, picking at the cantaloupe in a fruit salad during a funeral memorial service, chewing bites of pizza in the waiting room of a district courthouse. This is a privilege in itself.

Despite everything, I am still alive. To stay alive, I eat. To live, I feed, which is even more of a privilege: not just to exist, but to be able to appreciate that existence and those within its confinements.

In our first few times seeing each other, my partner brought me a pound or so of fresh oyster mushrooms they had grown. Our common philosophies of food and consumption have been a source of conversation for us. More recently, we started cooking together. They made me a fall roast of chorizo sausage, brussels sprouts, purple potatoes, and carrots. I made them sea scallops in browned butter and lemon juice and white wine vinegar with garlic and black kale. This past weekend we took to the task of cooking a duck egg frittata that satisfied every possible satiation of hunger after putting our bodies through a substance-fueled wringer the night before. I think I have shown them the magic of the Marcella Hazan tomato sauce (it doesn’t need garlic, babe, really!).

Despite everything, I am considering living: who will I feed in this lifetime?

This essay began as an Instagram post I made in September after my partner brought me those aforementioned oyster mushrooms. This is a much-updated and elaborated-upon version of that essay.

Hunger For a Way Out is also the title of the 2020 album by post-punk band Sweeping Promises. You can listen to it here.

If you are not subscribed to Very Normal Girl, read what this Substack is about, and please subscribe:

Subscribe

Please consider sharing this post:

Leave a comment if you have any thoughts:

And thank you for reading and subscribing and caring and feeling, anything :’) Audrey